This guest blog was written by Dr Jaime Aristotle B. Alip, also known to many ICMIF members as Aris Alip. Aris is a poverty eradication advocate, with more than 35 years of experience in microfinance and social development. He is the founder of the Center for Agriculture and Rural Development Mutually-Reinforcing Institutions (CARD MRI) in the Philippines. Dr Alip is also a member of the ICMIF Board of Directors.

With 2,643,494 recorded cases and 39,232 deaths as of October 8, 2021, COVID has wrought unprecedented hardship for the Philippines – despite the adoption of stringent lockdowns since the pandemic started in 2020. The spikes in COVID cases, especially the recent surge caused by the Delta variant, not only placed pressure on the national health care system, it also hampered plans to expand health insurance coverage due to the ensuing economic challenges. It highlighted the insurance gap in the Philippines, where penetration stands at around 1.71 percent of GDP.

But there is a silver lining. With the health crisis came an increase in insurance awareness and greater demand for health insurance. Even those from low-income groups now understand the need for financial protection against unexpected shocks, recognising that an illness or death in the family could bring them deeper into poverty. Last May, the Insurance Commission (IC) reported that the number of lives covered by microinsurance products in 2020 hit 50.35 million, an 11.56 percent increase from 45.13 million in 2019. Amidst the COVID pandemic, microinsurance has become a lifeline for Filipinos, even those with low income and limited access to mainstream insurance services.

Clearly, the government needs to support microinsurance and facilitate protection coverage to the most vulnerable sectors. This is crucial, especially during this pandemic.

Microinsurance MBAs

Poverty alleviation is central to our development agenda, as outlined in “AmBisyon Natin 2040” and the “Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022.” This involves building people’s socioeconomic resilience through the provision of universal and transformative social protection, including insurance mobilisation. Unfortunately, health insurance under PhilHealth, with its limited coverage and benefits, remains inadequate, while mainstream insurance companies have failed to penetrate the low-income and poor market segment.

Enter microinsurance. As the name suggests, this pertains to affordable insurance products intended for the poor and low-income families. These are usually offered by mutual benefit associations (MBAs) which must register with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and apply for license from the Insurance Commission (IC) as a non-stock, non-profit association and insurance provider in line with Sec. 404 of the Revised Insurance Code. The IC laid down the policy framework for microinsurance fifteen years ago, through Memorandum Circular 9-2006, which introduced Microinsurance Mutual Benefit Associations (Mi-MBAs). These are member-owned and governed microinsurance providers that offer insurance to members, pay claim faster (within a few days from the date of claims notice), and distribute products using the social distribution network of partner microfinance institutions (MFIs). This Circular regularised previously informal MFI and NGO arrangements in microinsurance provision, and Mi-MBAs eventually became key drivers of microinsurance development, providing simple, affordable, and accessible microinsurance products to low-income families.

The 2010 National Strategy and the Regulatory Framework for Microinsurance facilitated further growth of the microinsurance industry, with rural banks, thrift banks, and even mainstream insurance outfits and fintech companies becoming players. Within this ecosystem is a niche for Mi-MBAs, led by the Microinsurance MBA Association of the Philippines (MiMAP), which presently covers 62 per cent of the microinsurance market.

A total of eighteen Mi-MBAs under MiMAP have a combined outreach of 7 million individual members nationwide, majority of whom are micro-entrepreneurs, small farmers and fishermen. As microinsurance coverage is extended to the members’ families (with 4 as average family size), MiMAP currently insures 28 million Filipinos. The Mi-MBAs provide basic life family microinsurance plans and a range of optional life plans that include coverage for health and retirement. In 2019, the mobilisation of such membership accumulated a total of PhP 4.81 billion in contributions and premiums, paid PhP 1.43 billion in claims benefits, and reserved PhP 1.95 billion in refundable equity value to members. These Mi-MBAs have significantly contributed to greater financial inclusion and financial literacy for poor and low-income Filipinos.

Tax exemption

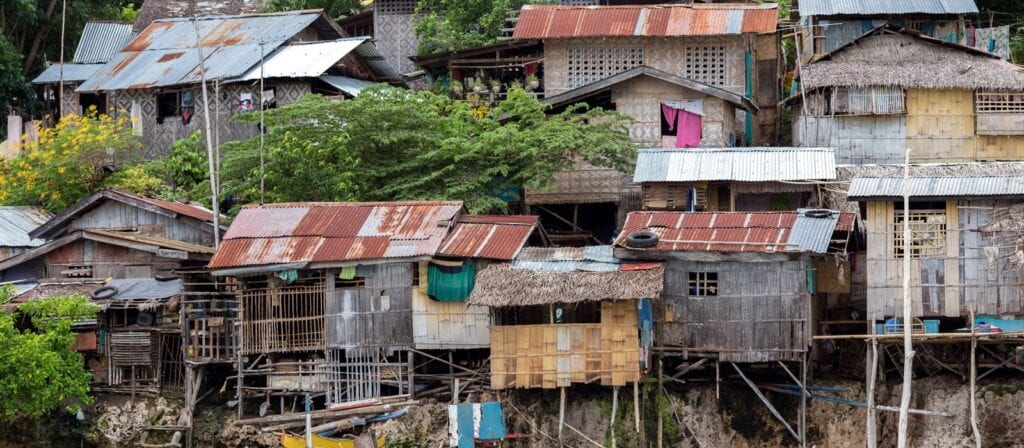

Mi-MBAs are crucial to financial inclusion, as they are community-based organisations able to penetrate hard-to-reach and frontier areas where conventional insurance providers dare not go. During this period of pandemic, Mi-MBAs helped in alleviating the plight of the poor and those most vulnerable to economic shocks. Even as they suspended the collection of contributions and extended the grace period for payments, Mi-MBAs continued to pay claims benefits. Under very difficult operational and business circumstances during the first five months of community quarantine from March to August 2020, Mi-MBAs paid a total of 27,657 death claims worth PhP 613.54 million, 667 of which are COVID-related deaths.

Since Mi-MBAs are non-stock, non-profit microinsurance providers that operate for the exclusive benefit of their members, they are exempted from paying tax on corporations, tax on life insurance premiums and documentary stamp tax under the Insurance Code and the National Internal Revenue Code. Unfortunately, not all Mi-MBAs are able to avail of these exemptions as tax authorities vary in their interpretation of the applicable provisions. MiMAP reports that some of their members have been issued notices of tax deficiencies, while others were denied tax exemption status. Many Mi-MBAs, in fact, are still waiting for the BIR ruling on their application for tax exemption.

This is sad, since Mi-MBAs already operate on very thin margins because of their restricted capacity to spend only up to a maximum 20% of their contributions for administrative and operating expenses. The situation exacerbates their resource constraints, inhibiting them from optimizing or upgrading their management information systems.

It behoves the government to ensure that Mi-MBAs enjoy the tax exemptions granted to them under the law. Mi-MBAs, after all, are managed by grassroots organisations composed of low-income families. Their members and target clients are also poor, mostly belonging to the informal sector. They provide necessary financial services to the most vulnerable, contributing to poverty alleviation and financial inclusion. Mi-MBAs could serve more Filipinos if they can fully enjoy their tax exemptions, which could help them digitise their operations — a necessity given that mobility and face-to-face interaction are greatly limited by the pandemic.

Tax reduction for non-life insurance

Tax rules also impede market development with respect to non-life insurance. Usually, as the market matures, a more diverse range of products is expected, to serve broader customer needs and to diversify insurers’ risk portfolio. This is not the case here, because general taxation for the non-life insurance sector reaches as high as 27 percent, one of the highest in Southeast Asia. This discourages insurers from offering complex products, such as disaster and agricultural insurance, both highly relevant to the low-income population. The tax on nonlife insurance products, including crop insurance, should be reduced to 2 percent, or the current rate imposed on life insurance products. Cutting the tax on non-life insurance premium will significantly raise the number of private insurance offerings. There will be no need for government to subsidise agri-insurance because the regime will be market-driven.

Microinsurance has come a long way in the Philippines. From a coverage of less than three million low-income Filipinos in 2007, the number has surged to more than 50 million last year. Microinsurance MBAs, in particular, significantly contribute to poverty alleviation, financial inclusion and literacy by providing affordable and relevant risk protection to poor and underserved households. But millions of poor families remain unprotected and vulnerable. With natural disasters always a possibility given climate change, and the threats posed by the COVID pandemic, we should find ways to support the growth of the microinsurance industry. As the 2022 election draws near, those who aspire to be the country’s next leaders should champion financial inclusion for the poor and include microfinance and microinsurance in their battle-cry. Their campaign to provide affordable and relevant risk protection to millions of Filipinos from low-income families would serve them well come election time.

CARD MRI is a group of 23 organisations that provide social development services to 7.8 million economically-disadvantaged Filipinos and insure more than 25.8 million nationwide. CARD’s innovative financial and enterprise development services targeting the poor have won many accolades, including the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service in 2008, and for Dr Alip, the prestigious Ramon V. del Rosario Award for Nation Building in 2019. Dr Alip is an alumnus of the Harvard Business School, the Southeast Asia Interdisciplinary Development Institute and the University of the Philippines.