COVID-19 is changing how we work, travel, communicate, shop and more, but which new habits are likely to stick permanently? Swiss Re explore five key behavioural changes and interconnected trends emerging from the pandemic, looking at their implications for risk and protection and how they may act as potential catalysts for change in the insurance industry.

The pandemic has impacted virtually all aspects of our lives. Some developments have been sudden and involuntary, such as social distancing, wearing masks, stopping public transport, restrictions on travel, etc. For others, it has merely accelerated the adoption of behaviours already gaining traction, such as the digitalisation of shopping, banking and more.

Temporary or permanent?

Will these changes in behaviour last after COVID-19 subsides, or will consumers' old habits die hard? Behavioural studies and past events can offer answers.

All consumer behaviour has strong location and time dependencies. Behaviour can differ significantly from one location to another depending on cultures, geographies, etc. The pandemic is making this dimension of consumer behaviour more complex; for example, since physical movement is restricted, consumers are migrating into virtual worlds at an unprecedented rate and are exposed to newer influences. This could require us to go beyond traditional methods of modelling their behaviour.

Behaviour and habit changes are also directly linked to the extent of exposure to new environments. Research shows that it can take between 18 and 254 days to form a new habit; on average it takes about 66 days. People more quickly adopt habits that do not significantly change existing routines. Today, consumers are settling into new patterns of behaviour for considerable lengths of time in response to the multiple waves of this pandemic. This is fertile ground for new habit formation.

New experiences need to offer significant incremental value for a change to become permanent – and poor experiences can result in a rapid reversal to past behaviour. For example, demand for telehealth rose dramatically during the initial lockdowns but has since fallen to less than half of its peak (although still significantly higher than prior to COVID-19). Some of the drop could be due to poor customer experiences of online consultations. Conversely, demand for online shopping appears to be sustainable for the long term. The fear of catching an infection may fade once COVID-19 is over, but the significantly higher perceived convenience may make the behaviour permanent.

The e-commerce sector has responded rapidly to the challenge of creating positive experiences in response to the pandemic. Companies have invested in logistics and supply chains and widened their product ranges. This has attracted large numbers of consumers, and a 2020 survey found many of them were likely to continue to buy online for non-health reasons such as convenience, time savings and wider product ranges.

A number of other drivers can change and disrupt consumption habits. These include social contexts such as life events - marriage, childbirth etc, and new technology – for instance, the advent of the internet changed many business models and artificial intelligence (AI) may change them again. A third driver is new rules and regulations – for instance, subsidies for solar and wind power generation has encouraged a shift to clean energy sources. Unexpected ad-hoc events such as pandemics, as we are experiencing now, as well as natural catastrophes or man-made disasters such as wars, are a fourth.

How is consumer behaviour changing?

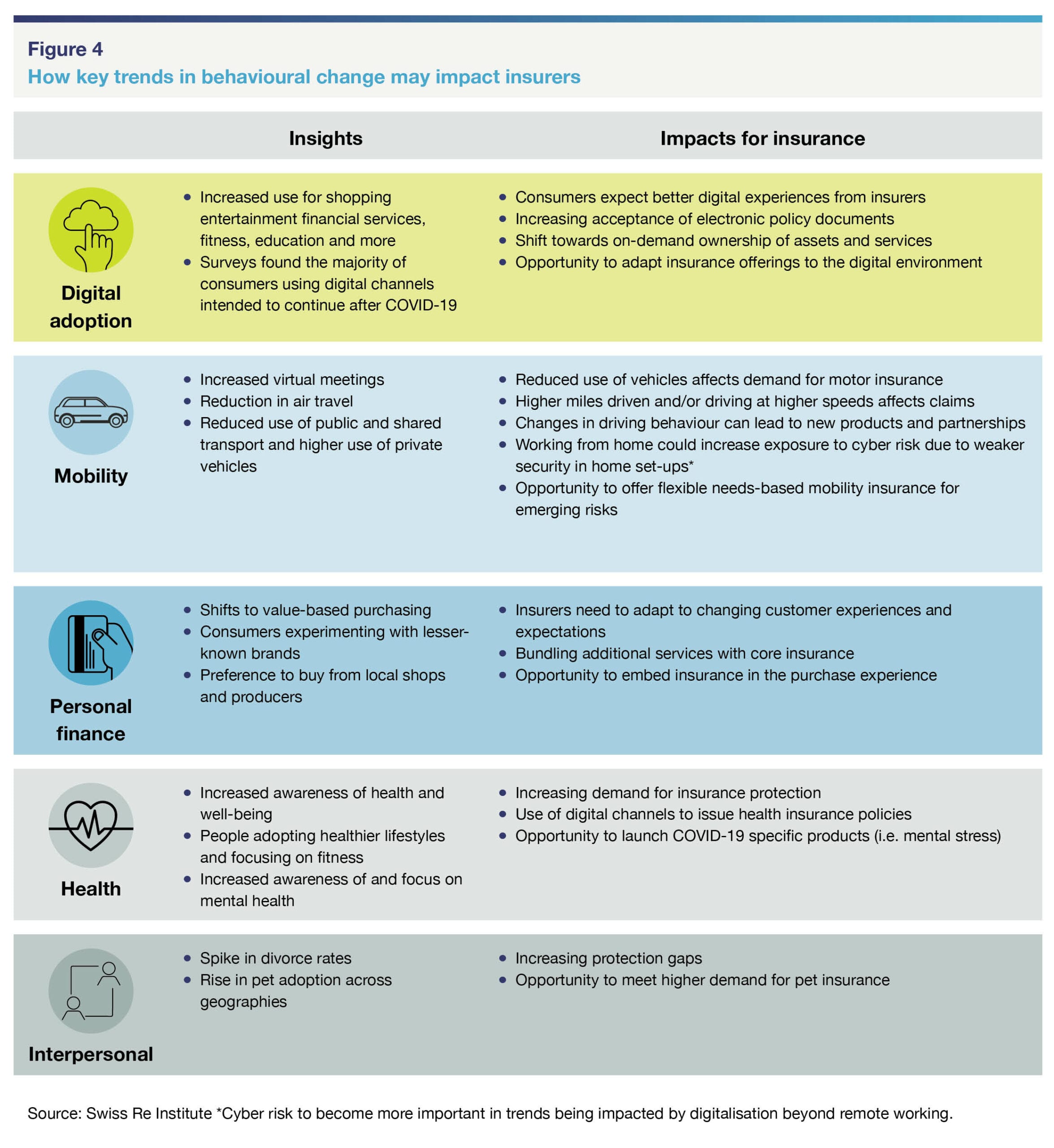

We see five key trends in the behavioural changes emerging from the impact of COVID-19:

- Increased digital adoption: people shifting to digital platforms for day-to-day needs.

- Change in mobility patterns: less use of public transport, more remote working etc.

- Change in purchasing behaviour: move to value-based purchasing and online shopping.

- Increased awareness of health: wearing masks, increased hygiene, healthy eating etc.

- Changes in interpersonal behaviour: increased divorce, increased pet adoption etc.

These trends are interconnected and overlapping. The pandemic has increased people's use of digital tools in life and business to stay connected in a world that is physically disconnected. Increased use of digital tools is blurring the lines between work, lifestyle and social interaction and between domains like mobility, health and finance. We expect this to continue in the post-COVID-19 world.

Past experiences offer clues to how consumers may behave after the pandemic ends. For example, the spread of SARS in 2003 left a lasting impact on people who have lived through the event. Anecdotal evidence suggests that people still follow habits picked up during the crisis, such as washing hands, using toothpicks to press elevator buttons, tissue paper to open doors of public washrooms and even carrying spare masks in their handbags.

In contrast, air travel quickly bounced back from a sharp decline immediately after the 9/11 terrorist attack in 2001, as people were reassured by tighter security. Air travellers who may have previously raised privacy concerns around security checks were more willing to accept stringent measures including body scanning in exchange for greater security.

All five of these key trends are potential catalysts for change in the insurance industry, as the figure below illustrates.

What these key trends mean for insurers

Trend 1: Increased digital adoption

As digitisation spreads across industries, consumers increasingly expect a similar experience from insurers too. A recent survey by Swiss Re Institute in Asia found consumers very open to insurance products designed for digital platforms, with more than 70% expressing strong intent to purchase products tested in the survey. Insurers have the opportunity to take advantage of this and adapt their offerings to the new digital environment.

In response, insurers are adapting to the new customer expectations. Many have reprioritised and accelerated digital initiatives such as digital advisor tools, self-serve capabilities and claims automation. Distribution and customer engagement remain the primary focus for most insurers, and some are digitally enabling agents to reach customers virtually.

The pandemic has helped to break the historical resistance to electronic delivery of policy documents; related customer requests for hard copies are decreasing. People who were comfortable with paper are now going digital.

Preferences could move towards on-demand ownership of assets and services. Such changes will continue to open up new risk pools for insurers.

To take advantage of the digital wave, insurers should go beyond digital distribution and digitise the entire value chain in order to issue, underwrite, collect and indemnify in a customer-centric process.

This article was written by Mahesh H Puttaiah, Senior Economist, Swiss Re Institute; Aakash Kiran Raverkar, Research Analyst, Swiss Re Institute; and Evangelos Avramakis, Head Digital Ecosystems R&D, Swiss Re Institute, and is reproduced with the kind permission of ICMIF Supporting Member Swiss Re.

To access the full in-depth article, including interactive graphics, please visit this Swiss Re Institute webpage.

Published April 2021

Trend 2: Changes in mobility patterns

Restricted mobility has reduced transport use, but some people are driving more miles and some at higher speeds. This has implications for demand for both new motor insurance and renewals, as well as claims. Similarly, a change in long-distance travel, particularly air, would affect demand for travel insurance. More widespread working from home could increase exposure to cyber risk due to weaker security in home set-ups.

Insurers in some markets have responded by introducing pay-as-you-go products that only charge users for distance driven, a trend we expect to grow. There are also new partnerships being forged between original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and data analytical platforms that can provide useful data to enable insurers to better price and underwrite cover, and to design new products customised to user needs.

In some instances, insurers have provided premium holidays on motor policies, but in general premiums have largely stayed the same, despite changing car usage. Most underwriting models are backward-looking and do not yet have sufficient data to price circumstances like the present.

In the medium to long term, we expect mobility patterns to involve a mix of transport modes that may change as commuters and travellers factor in the risk associated with each mode. This calls for flexible, needs-based mobility insurance to cover people irrespective of the mode of transport, and cover new risks that emerge.

Trend 3: Changes in purchasing behaviour

Consumers are more conscious of what they buy and more focused on obtaining value from purchases. Since other than compulsory lines, insurance is not typically considered an essential purchase, insurers can increase the appeal of products by adapting to changing customer experiences and expectations.

Bundling additional services with core insurance products may increase value for consumers. A report from prior to COVID-19 estimated that by 2024, 61% of insurers will generate more than 30% of business from service-based rather than product-based offerings, and 33% of premium will come from new propositions. Insurers will need to identify the services of most interest to customers and find ways to integrate them to make the offering meaningful. Regulators worldwide are supportive of customer-centric offerings and in some cases have launched sandboxes to enable testing.

Trend 4: Increased awareness of health

Higher awareness of health risks is increasing demand for insurance protection. Insurers are turning to new technologies to quickly respond to this demand, such as using digital channels to issue health insurance policies up to a certain limit and coverage, though this can pose challenges for insurers, such as accuracy of underwriting in the absence of conventional medical check-ups. Insurers are also providing customised products, some that offer cover irrespective of travel or medical history, and many are integrating wearables and fitness apps in their offerings.

Trend 5: Changes in interpersonal behaviour

Divorces can often lead to financial hardship so have a significant impact on family finances and hence on the need for insurance, which can increase protection gaps. For example, health insurance provided by an employer usually covers the whole family. A dependent spouse would not be covered by such family cover after a divorce. Similarly, in the case of term insurance, if a policy owner decides to change the beneficiary, the dependent spouse would be left unprotected.

Higher pet adoption will likely expand this risk pool to include pet insurance: some estimates suggest pet insurance demand may grow at a CAGR of 16% between 2020 and 2027.

The way forward

Insurers will need to adapt to the new behaviours and expectations. The waves of this pandemic, in which lockdown measures are relaxed and imposed, are likely to increase consumers' sense of insecurity and raise demand for seamlessly interconnected products and services that are "adaptive" to changes in the environment.

Insurance products and services can do this by including greater modularity, or decomposition into different value components that can be switched on and off. For example, a travel insurance product might temporarily reduce different coverages during the pandemic when consumers are not travelling. There is also product/service granularity, or many variations within a product or service model that enable it to accurately reflect reality. For example, motor insurance that adapts to a person working from home by reducing their mileage cover by exactly the proportion they are driving less. These features all increase adaptability.

To do this, insurers will need to personalise insurance propositions with respect to risk transfer and integrate preventive and value-added services into retail and commercial lines. Examples include fitness programmes to offset people's inactivity in lockdowns, or childcare services to relieve parents' workloads. These could change over time, resulting in a more adaptive and personalised approach. In time insurers could have long-term, seamless relationships with customers that care for a wide range of needs, in which the customer "feels" the value of higher engagement, empowerment, and emotional connection (empathy).

The drivers of new insurance products and services can include:

- Changing risk exposure: risk is shifting from one life area to another. This requires more flexibility in terms of providing a modular as well as granular product. For example, insurers need to adapt to lower mobility in the case of people working from home, resulting in fewer miles driven, less traffic, less congestion, less need for parking, thus a different risk exposure. Similarly, insurance products and services need to adapt to the new changing reality in the case of further pandemic waves.

- Interdependency of product lines: as one risk area changes, another risk area is directly impacted. In case of employees working from home, mobility exposure decreases but cyber and property risks rise due less robust cyber security infrastructure at home, and more use of homes. Similarly, health risk exposure is also changing as the environment negatively impacts mental health. The interdependency of product lines (property and casualty, and life and health) could increase to meet these needs, but these dynamics could change again due to the pandemic.

- Interdependency of business lines: working from home implies that certain risks shift from corporates to employees. This is blurring private and business life, suggesting that more interconnected retail and commercial coverage may be useful. This provides new opportunities for commercial lines offerings, for example in mental stress coverages.

Imagine now you develop an adaptive and data-driven product. This would provide a flexible set of covers supporting a consumer's changing lifestyle in pandemic and non-pandemic phases. This could include motor, cyber or health protection, and the product and service proposition would evolve in response to the policyholder's changing risk exposure. The risk and service cover would fluctuate depending on the restrictions or lockdowns introduced. Different insurers could also provide the covers at different points.

For example, in pandemic waves with lockdowns, employers are aware that mental stress can significantly impact employees' health and productivity, calling for specific insurance coverage or support services during these periods. Yet this risk exposure is temporary and would reduce in a post-pandemic phase of normal work. An adaptive policy would allow employers to offer flexible cover or employee support services during lockdowns while post-pandemic cover could be provided by another insurer.

Conclusion

The experience of living through COVID-19 is changing the world in which we live and our behaviour. Changes that provide positive experiences are likely to last longer, particularly those driven by convenience and well-being, such as digital adoption, value-based purchasing and increased health awareness. This provides an opportunity for insurers to offer innovative, modular, granular, value-based and integrated products to meet customer needs. It is vital that insurers understand consumers' preferences to stay relevant and adapt accordingly.